Whitman wrote his greatest work immediately prior to the Civil War, that is, at a time of a great national crisis. He was convinced that America, perhaps more than any other nation, needs poets. He was acutely aware of the political corruption and social problems of his time: he, therefore, set out to "quell America with a great tongue." (No matter how much the political and social corruptions of his day bothered him, he never lost a profound sense of optimism, rooted not only in his nature but in his (very) non-dogmatic religious faith.) He viewed his task as a Messianic one--and, unlike false prophets, his words are replete with truth and dignity. Much of what he wrote still very much applies to America today. I don't think I'm exaggerating by stating that Whitman's stance on many issues has become

urgent; if we ignore them, we, both as individuals and as citizens, will pay dearly.

This article will focus on three (there are many more) of his core beliefs: the spiritual poverty that results from the 'mania of owning things'; the central importance of personal relationships; and, finally, a call to fully embrace an equality that includes not only gender and racial justice, but extends to people of all classes.

3.

Whitman and Materialism

Whitman's family on both sides settled in America before independence. His father's ancestors were wealthy landowners, but the family fortune steadily declined. At the time of Whitman's birth, the original five-hundred acre homestead in Long Island had dwindled to sixty. His father was quite unsuccessful; the family had a difficult time raising Whitman and his numerous siblings. They all moved to Brooklyn when Whitman was two years old. In his autobiography Whitman notes, regarding the houses where he lived in in Brooklyn during his youth, "We occupied them one after the other, but they were mortgaged, and we lost them." Whitman, who absorbed the scientific and cultural life of his times to an astounding degree, left school

permanently at the age of eleven, to help his family. His housing was always what we would consider today to be simple, whether he worked as a printer, journalist, teacher, editor, carpenter or writer. Working as a carpenter in the early 1850s, Whitman actually built the house he lived in. When he suffered his first stroke at the age of 54, he moved in with his brother, George, who was an engineer and pipe inspector. His brother and his family lived in a row house in Camden, New Jersey. I am not sure what his brother charged him--probably not much--but Whitman always paid room and board. It was only when Whitman finally became famous that he was able to afford the house pictured in this article. He was at that time 64 and crippled. He died in that house eight years later, bedridden and in constant pain.

The life of the poet, who was not a churchgoer, was a stellar example of living according to Jesus's injunction that we should "store (our) treasure in heaven, where moths and rust cannot destroy..." Heaven I would interpret here--and Whitman would undoubtedly have agreed--to mean that one should live life to the fullest

spiritually. This doesn't mean that we should be indifferent to our material comfort; it does mean, however, that we should not lose perspective and balance. (Extolling perspective and balance are dominant themes in Whitman's life and work.) The businessmen's houses pictured in this article are clear examples of unbalanced lives. How much better the world would be if they lived even

slightly ostentatiously, yet spent more time developing their own minds

and actively helping others!

Whitman beautifully expresses the delight in fellowship and the dangers of crass materialism in the following lines from Song of Myself:

I am satisfied--I see, dance, laugh, sing;

As the hugging and loving bed-fellow sleeps at my side through the night, and withdraws at the peep of the day with stealthy tread,

Leaving me baskets cover'd with white towels swelling the house with their plenty,

Shall I postpone my acceptation and realization and scream at my eyes,

That they turn from gazing after and down the road,

And forthwith cipher and show me to a cent,

Exactly the value of one and exactly the value of two, and which is ahead?

4.

Whitman and Friendship

Whitman was a quintessential people-person. If you could have asked him what makes people truly rich, he would answer "comradeship" without hesitation. (The latest research illustrates the wisdom of being more concerned about people than about anything else: isolation tends to take years off lonely lives. Human beings evolved in groups.) Whitman's love of people was not of the How-To-Win-Friends-And-Influence-People sort; nearly all fascinated him in their own right. For Whitman the way to build treasures in heaven was to build treasured relationships on earth. His love of people had a very religious--and sensual--quality. All of Whitman's poetry is informed by the belief in the sacredness of human relationships; here is but one example:

I merely stir, press, feel with my fingers, and am happy,

To touch my person to some one else's is about as much as I can stand.

Note that Whitman writes "person" and not "body"--for him, touching another is also coming into contact with that person's soul. No narcissism or mere self-gratification here!

There are not many references to envy in Whitman's poetry. Here is one that turns the concept of envy on its head. Usually one is envious of another who is richer, handsomer, smarter, etc. Such envy was totally foreign to Whitman. He is not speaking of himself in the following poem--he had so many friends; he wishes to convey to the reader that human relationships are the measure of true wealth. (Notice that Whitman doesn't mention any qualities or achievements of those in the "brotherhood of lovers"--their ability to be a good friend is what is essential. In Whitman's time, by the way, "lovers" meant, simply, "friends." Note also the line, stating that he does not envy "the rich in his great house.")

When I peruse the conquer'd fame of heroes and the victories of mighty generals, I do not envy the generals,

Nor the President in his Presidency, nor the rich in his great house,

But when I hear of the brotherhood of lovers, how it was with them,

How together through life, through dangers, through odium, unchanging, long and long,

Through youth and through middle and through old age, how unfaltering, how affectionate and faithful they were,

Then I am pensive--I hastily walk away fill'd with the bitterest envy.

5.

Whitman and Equality

Whitman was a staunch feminist--he was friends with many of the feminists of his day, and made sure he attended the first great meeting for women's rights in American history, which took place in Seneca Falls in 1848. He was downright contemporary in this regard, "The woman as well as the man I sing." He believed that qualified women should attain positions in all fields, including becoming members of the Congress and Senate. Regarding race, he was way ahead of his time, albeit not completely unaffected by the rampant racism of antebellum America. The former slaves Frederick Douglas and Sojourner Truth waxed rapturous when discussing Whitman, who treated African Americans in his poetry with love, decency and respect. Needless to say, he vociferously opposed slavery--but not as radically as some, since he was willing to make (temporary) concessions to keep the Union intact.

Regarding gender and racial equality, we have achieved much that would have delighted Whitman. Women are assuming more and more important positions; women, in fact, are doing better in higher education than men, which assures that more progress is in store in the future. Regarding racial progress, we now have an African-American president. Even though many still oppose our president because of his race, the possibility of a black president filling America's highest ofiice was beyond the wildest imaginings of the nineteenth century--and for that matter, for most of the twentieth century. This does not mean that these issues have been resolved; but we are doing much in the Whitman spirit, and will undoubtedly continue to do more.

But something is seriously missing. We get the first line right, but are horribly failing with the second line of the following, from "One's Self I Sing":

One's self I sing, a simple separate person,

Yet utter the word Democratic, the word En-Masse.

Actually we're not even getting the first line right. The majority of us seem

to be singing his or her own self, that's true. But in the arias we sing to the mirror, "simple" has been replaced by "unique," "superior" and "downright special." We are failing miserably in the realization of the second line, which balances individualism with equality. (In Whitman's philosophy, both lines should be realized; realizing one at the expense of the other results in misery. History certainly confirms this view.) This is so obvious, I will illustrate it with only one point: professional women are getting good jobs, professional African-Americans are getting good jobs, while the undereducated masses of both genders and all races are doing worse and worse. This is not a situation that would please Martin Luther King, Susan B. Anthony and certainly not Walt Whitman.

Whitman lived in an age that was in many respects much like ours. During the colonial period and for decades after independence, inequality was not at all rampant. Whitman lived in an age of rapid industrialization, during which the country transitioned from an agricultural economy to a capitalist one. Brooklyn was quite rural when Whitman moved there as a toddler; by the time he was forty, it had become a bustling metropolis. Inequality among social classes increased dramatically, to a point, in fact, which was almost as bad as it is in America today. (Today one percent owns 40% of the wealth; by the end of Whitman's lifetime, the top one percent owned 30% of the wealth.)

Whitman was by no means a political radical; one of his mottoes was "Be radical, be radical, be radical--but not too radical." There is little anger in his poetry, although as a journalist he was sometimes quite enraged. (He wrote some --deservedly no doubt---nasty things about the corrupt presidents who preceded Lincoln.) He would not have supported revolution; he did avidly support, however, a revolution in thinking which would make violence unnecessary.

He wrote that one of the purposes of his work was to "cheer up the slaves, and horrify despots." (A variation of the beautiful Jewish adage that religion is to "comfort the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable.) His poetry is quite consistent with this view.

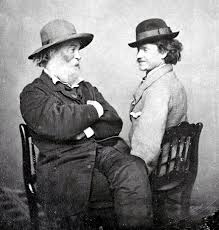

Whitman's life and work are stunning examples of the very antithesis of elitism. He knew many of the top intellectuals of his day; he also befriended many members of the working class--not only because of politics, but because he found worth in them as individuals. What follows is a photo of Whitman and his friend Peter Doyle, who had been a Confederate soldier and a "mere" bus conductor after the war. Doyle was also present in Ford's Theater the night Lincoln was shot, April 14, 1865. (Whether or not the relationship between Whitman and Doyle was partially fueled by eros does not matter; the marriage of two mutually self-respecting personalities, no doubt, was what the kept the fire going.)

Whitman knew America was ill and needed medicine. He wrote his poems in an effort to provide a recipe for health. He loved and respected people of all classes, but emphasized those from the working class in his poetry not only from genuine devotion to them, but to spread a sense of much needed egalitarianism with his infectious verse. He "catalogued" many different types of workers in his poems, stressing that no class is superior to another. The examples are legion; I will give two. First, the opening lines of "I Hear America Singing"

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of the mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam...

(He goes on to praise masons, boatmen, shoemakers, wood-cutters, etc. Another illustration of his identification with workers comes from Song of Myself: "A young mechanic is closest to me, he knows me well, etc.")

The second example comes from a poem written shortly before his death::

I see Freedom, completley arm'd and victorious and very haughty, with Law on one side and Peace on the other,

A stupendous trio all issuing forth against the idea of caste...

What could be more contemporary than a poet who convincingly and beautifully argues for less greed and more fellowship?

Whitman who vigorously absorbed all aspects of American life; whose spirit transcended his country while never ceasing to love it; Whitman, who wrote poetry of the first order, offered as an elixir to uplift and transform, has much to teach us. We should indeed follow his injunction to read his poems out loud during all seasons. And heed them! Whitman, as stated previously, wrote that America, perhaps more than any other nation, needs poets; the current mess in Congress is but one of countless indications that this hasn't changed. Have we completely given up on the idea of the transformative power of great poetry? As Geoffrey Hill wrote in a poem, "We learn too late or not too late."

I will end on a personal note. Whitman's poetry has been delighting me for half a century. Among other things, it has helped me maintain a transcendent optimism, no matter what happens locally. I must admit, though, that my local self is getting nervous.

The Walt Whitman Essays

(All on thomasdorsett.blogspot.com)

1. Walt Whitman and Music

2. Whitman's Vision

3. Five Poems About Death

4. My Walt Whitman Moment

5. Walt Whitman and Equality